The following is an excerpt from the collection of short stories titled "Call of the Mountains: And Other Tales of the Bizarre." If you enjoy it, please consider purchasing the full collection from Amazon.com!

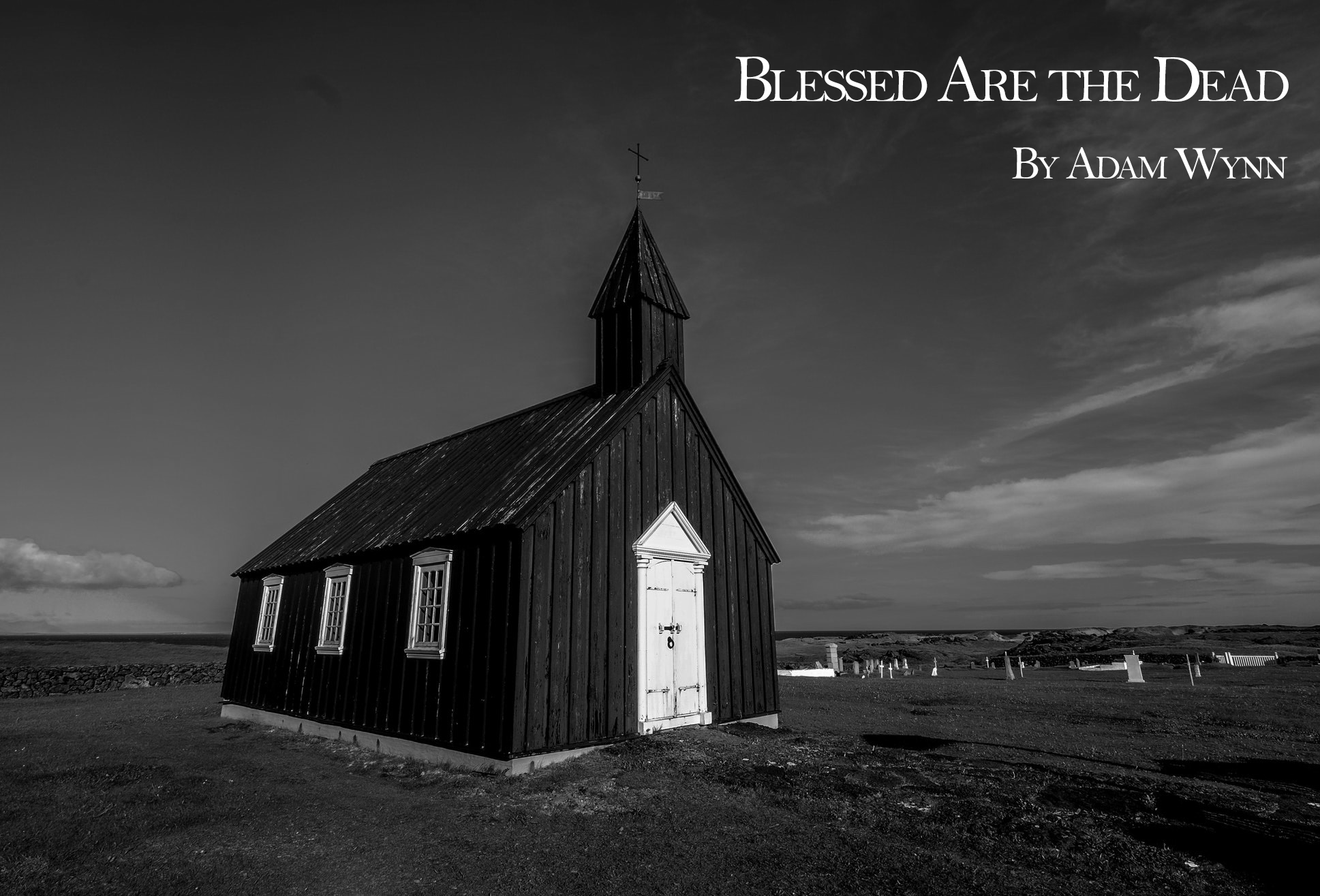

Photo by Ghost Presenter on Unsplash

Two men barred the doors as the last of the congregation entered the room. The abandoned church house could hold upwards of 200, though just about 50 entered for tonight’s service. Pale plaster walls shone orange and beige with the permeating glow of candlelight as Reverend Zachariah ran his fingers across the hollow casket at the front of the room. He had lit the candles himself this time, preparing for a special evening with his flock.

Hushed murmurs were the order of the pre-ceremony conversation with farmers and teachers and salt-of-the-earth Americans from rural Kansas struggling for words of casual civility in the midst of such somber proceedings. Reverend Zachariah had called them all in that evening with the once-dormant church bells, and those who remained knew why they were coming together.

“Blessed are the meek,” Reverend Zachariah boomed with his sonorous voice as he climbed the steps to the pulpit, “for they shall inherit the earth.”

A fervent chorus of amens met the reverend’s declaration, a signal that he could proceed.

“Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of Heaven.”

“Amen,” the men shouted in unison.

“Blessed are they which thirst and hunger after righteousness, for they shall be filled,” Zachariah proclaimed, once again to the favorable response of the crowd. “Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God.

“Blessed are the merciful, for they shall receive mercy,” he yelled and they joined.

“Blessed are those who mourn,” Reverend Zachariah paused, looking in each eye one by one. “For they shall be comforted.”

Though the congregants were more subdued in their agreement, each one acknowledged the verity of Reverend Zachariah’s words with silence.

“Though people mock us for our rural, perhaps somewhat antiquated ways, it is our isolation here that has preserved us from the degradation that plagues this world. The forces of darkness grow stronger every day, and even we have felt their sting,” Reverend Zachariah continued. “We have all lost those dear to us, have we not?”

Some of the women wailed while those fortunate enough to still have husbands were held tight by the deteriorating men who sat next to them. Grief and loss had wracked the good people of Reverend Zachariah’s flock and it was time that he, a good shepherd, did what was best to quell the pain that each of them endured.

“As we gather tonight for the Last Su…” he coughed, “for communion, I offer each of you a chance to remember your family and friends who have departed before us. We all have felt the burden of loss with family or loved ones who have preceded us in death, and though we know they have already experienced the resurrection, we who are still living must mourn and manage the grief in our own ways. So please. Join me for a moment of worship and song before we honor our dead by name.”

Adorned in his black robe, the gaunt Reverend Zachariah led the church hall in a singing of “Awake, Ye Saints, Awake,” minor chords playing over the organ and men and women swaying together in the sorrowful ritual. Zachariah was an older man who had stood at the head of a church for nearly six decades. Though this congregation was not truly his own, he had grown to love them deeply and dearly in the short time since they had come together. In that small span of weeks, they, too, had come to rely on Zachariah for spiritual guidance and healing.

At times Zachariah had felt like a gardener inheriting a field during a drought. There was precious little hope to be had in this time, though the people would gather regularly to scavenge what precious nourishment they could. Behind his sunken eyes and his sallow cheeks, all thinly covered by tufts of pepper-white hair that hung down beneath the reverend’s brow, there was compassion for these people.

Broken voices did their best to sing of joy and blessings, though their words and their hearts clearly lacked synchronicity. Zachariah lifted his own voice to Heaven above, but his thoughts were on the shattered faces looking down below him. Several of the men, even, hung their heads in sorrow while falsely proclaiming triumph over agony and death. Their faith had been tested, many of them to the point of loss, and the good reverend knew now more than ever that his cause was noble.

When the final notes of the hymn faded from echo into memory, Reverend Zachariah once again took his place behind the crucifix podium for a word of encouragement to his wayward flock.

“Dear beloved,” he began. “This world has mocked people like us for our faith ever since the fall. Was Cain’s disdain for Abel’s faith not what caused the first murder? Those without have always envied those who have, whether it be personal belongings and trappings of this world or the peace that comes with faith. We are fortunate people. We are blessed. For our faith.

“So as we gather this day for communion, let us not find mockery in faith. Let us find rest and hope in this faith that we possess. Let us find comfort in the presence of each other. Though our faith may be tested more now than ever before, in the presence of a wicked and depraved generation that has taken hold of this world, let us not forget what it is that we cling to. In the garden, when our Lord was tested and broken, what did He do? Did He acquiesce to the desires of this world?”

A few weary believers shook their heads and moaned an accord with the reverend.

“Did He bend His will to those who would have him silenced? Did He abandon such holy purpose for the sake of convenience?”

Again, the congregants whipped into a slight furor.

“No, He did not. He took his grief to the Father, and He acknowledged His pain. He looked to the Father and said, ‘Take this cup of suffering away from me, Father,’ but what?”

In one mighty voice, the crowd shouted back to Reverend Zachariah: “Not my will but thine!”

“Amen, brothers and sisters,” the reverend approved. “Amen.”

Reverend Zachariah turned and pulled a golden chalice from behind him, one that had been resting on a table next to a glass pitcher that held glittering red wine. He poured just about a quarter of the pitcher into the chalice and lifted the cup towards his people. They all looked to the cup, their gaze following it as if it were the serpent on Moses’ staff being lifted in the desert.

“Tonight, we will honor our dead. Once you have spoken a memory or two on those who went before you, come drink from the Lord’s cup and honor this communion,” Reverend Zachariah instructed. “Do we have any volunteers to go first?”

A minor woman, an elderly lady of 85 years, stood to break the extended silence that followed the reverend’s question. Each step she took was filled with pain, a fact betrayed by the limp her former broken hip had graciously gifted her with.

As she reached the summit of the stairs and stood to the side of the pulpit that was tall enough to hide her face from the people below, Bertha Mae rested a grizzled hand on the wooden cross and steadied herself to speak.

“I am tired,” Bertha Mae admitted, no longer wearing the white, curled wig that usually sat atop her wispy head for worship. “When Roger was taken from me, I wished it had been me. Everything in me begged to die. I didn’t know how I would go on without him. I held on for a while, though, and I finally thought I had found the strength to carry on. I would wake up in the morning and manage to get out of bed. The pain in my side was growing worse, but the pain in my heart got so much better day after day. It felt worth living again.

“But y’know,” Bertha Mae added after a pause. “I miss that man. I’d give anything to be with my Roger again and to see his face one more time. I remember…I remember when we got married. It was December of our first year of marriage and it was cold that year. Unseasonably cold. Well I woke up one night and he wasn’t laying down next to me, so I started to shivering. My teeth nearly chipped off they were knocking together so hard. When Roger finally came back to bed, I slapped him upside the head for leaving me like that. You know what he said? He said, ‘You should’ve known I’d come back, Bertha Mae. I’ll always come back for you.”

With tears in her eyes, and one rickety hand still gripped to the podium, Bertha Mae took the chalice from Reverend Zachariah and felt the wine trickle down her lips as a drop slipped out and stained her favorite white dress.

“Is this what wine tastes like?” Bertha Mae asked. “I guess I should’ve taken it up a long time ago.”

After Bertha Mae, Steve and Sarah made their way to the raised platform for a moment. They were several years younger than Bertha Mae, but Steve and Sarah were still an older couple that had seen the world change in incredible ways. Steve’s left hand held Sarah’s right firmly, and they looked out at those beneath them with earnest pain evident on their faces.

“Most of you knew our daughter Rebecca,” Steve said.

“She and her husband Mark…the Taylors’ boy, God rest them…moved off to New York City a couple years back,” Sarah explained to a slightly audible gasp at the mention of New York.

“We tried telling Mark and Rebecca to stay close to home. We knew how dangerous those cities could be, and you all know how dangerous New York is,” Steve continued. “They didn’t listen. She was going to teach inner-city children English and Mark was going to be a missionary there. All we know is that they went for a walk one night when…when…

“We haven’t heard from them since,” Sarah picked up, covering for Steve as he began to sob violently in front of his oldest friends. “Right before it happened, we learned that she was eight weeks pregnant. We were…we were going to be grandparents.”

Steve and Sarah embraced each other while a few other members of the congregation came up and put a hand on them. After the tears were done, they both took a sip from Reverend Zachariah’s cup and returned to their seats.

“I haven’t lived here very long,” said the young blonde named Victoria, “but you folks always made my husband and me feel welcome. When we moved from New Mexico, we thought it would be a hard life here. It turns out that this community gave us something to hold onto, and I thank you for that.

“I love you,” Victoria said while trying to look at each face corporately and none specifically before she too drank from the cup and stepped back down.

Erik came next, carting his three children to the stage with him. He struggled to tell of his wife and the youngest, both of which had passed away. As they did with Steve and Sarah, a few of the congregants came up and held Erik close in an act of love.

He was more than six and a half feet tall, and Erik carried his 300 pounds like it was nothing, but even a man as big as he broke down while speaking of his lost beloved. He told of arguments over changing diapers and about the time that his wife had begged him to buy a dog.

“I should’ve just bought her the dog. And some tulips. God, she loved tulips,” Erik remembered.

The three children who were with him stared confusedly at the room. They knew he spoke of their mother, and they cried accordingly, but they were still uncertain of what was going on. Erik helped each of his children partake of the wine, all three complained about how it burned, and then he took a sip for himself.

The Gossamer twins, both former Miss Kansas Corn queens, stood up next to Reverend Zachariah and talked about their parents, followed by the school teacher Miss James and the stories about her classroom. It had all started slow, but it seemed that people volunteered quicker the further along things went.

“It’s true that my wife went some months ago,” Jessup said. “We hadn’t been married real long when it happened, I guess, and it was hard to move on. It was hard not to feel cheated out of a life that I felt we’d been promised. A life that we deserved. But the thing is, and I’m sure Victoria wouldn’t want me telling this, we comforted each other after our spouses were gone. Now I don’t know if that’s a sin, I reckon there’s worse things to worry about right now, but I didn’t want to leave that unconfessed. I missed my wife, and I needed love all the more. Is that so bad? Is it? And what’s crazy is that, in the short time we had, I loved Victoria, too.”

Jessup’s farm house nearly backed up to the church, more than a thousand acres of wheat spreading out on either side of the white-washed charnel that they all stood in now. Jessup described the gown that his young bride was wearing the day they were married right where he stood then. Jessup described the lace that Victoria was wearing the first time they decided that they each deserved some of the love that fate had stolen from them. Or that God had stolen from them, either way.

The fifth-generation farmer gripped the reverend’s cup angrily, the rage in his expression after taking a sip deviating greatly from the resignation that most of Zachariah’s flock had shown.

“Bertha Mae. Steve and Sarah. They all got to live a life together. They had their happiness. But what about me and Victoria? What about those Gossamer twins? Or Miss James? What about those of us who were deprived of not just people we loved but of a whole existence we’ll never get to know? How is that right?” Jessup argued.

Hatred boiled over inside of him, and he tossed the cup down with a clattering and a spilling of wine when Reverend Zachariah came over and put a hand on his shoulder. There was just enough spilled for one person, the reverend figured, so it was no great loss. Reverend Zachariah patiently refilled the cup and set it back on the small table behind the podium where it would wait for the next person.

Over the next hour, each of Reverend Zachariah’s remaining parishioners took their place atop the stage next to the cup. And each one recounted someone they had lost. Moment by moment, though, a little bit more pain eased from the room when people could speak to life memories they had thought forever gone. With each wound lifted, the wake served its purpose and gave flight to the grief that the collective congregation had held on to for far too long.

Reverend Zachariah was proud of his efforts in leading the flock, and he was overcome with bittersweet joy at their great release. Yet the candles burned lower and the hour grew darker. The reverend refused to rush anyone, affording each of them the proper time to grieve, but he was running low on time and he was running low on wine. With each passing moment, several wicks burned down so the already dim sanctuary no longer glittered with the sparkling of the wine. Flat red made up the shrinking decanter with no light to spare on a reflection and hardly any wine left to spare a refill.

Former Mayor Smith. Old Barney the mechanic. Sandra the hairdresser. Refill the cup.

Amy Walters. John Porter. Lizzy Simmons. Refill the cup.

Barbara. Benny. Gordon. Refill the cup.

At last just three remained: Reverend Zachariah and his two closest friends, the men who had barred the doors earlier that evening. Josiah went first, speaking to the loss of his mother and the emptiness it left inside of him. Then he took a drink. Next was Sam.

Sam was a younger man, no older than 18, and he had latched on to Reverend Zachariah the moment he came to town. Those two were always discussing some great spiritual truth over pie and soda, and both Sam and the reverend enjoyed the other’s company.

“Rev,” Sam started. “When my dad passed, you were here for me. In all honesty, you became like a second dad to me and I don’t know if I could ever thank you enough for that. It’s never easy losing a parent, y’know, but I guess if it has to be done, I’d want everyone to have a friend like you to help them through it. Thank you, Reverend.”

Sam drank from the chalice last, leaving just enough for one more person.

“When I came here to your church,” Reverend Zachariah began, “you all took me in as one of your own. You never asked me to prove myself or put me through a trial. You just let me lead you, and I thank you for that. Serving you all tonight has been the greatest honor of my life.”

Reverend Zachariah surveyed the scene around him as he lifted the glass for one final toast. The empty bodies of his lambs lay slumped in their pews while Sam and Josiah sat on either side of the stage having already passed themselves. It was a slow drug, the one they had agreed on for the wine, but it was quick enough to spare them any pain. Moment after moment, the good Zachariah’s flock drifted off into glory, waiting now just on him to finish the task.

With a final toast raised high, Reverend Zachariah spoke his own parting words.

“I love you all. It was by far the hardest thing I have ever had to endure, the greatest test of my faith, watching you all depart ahead of me tonight, but I am thankful that I can now join you in eternity,” he concluded.

Yet he was too late. The sound that Zachariah had feared all night made itself known with a banging of the great wooden doors at the back of the church. The rattling gave him such a fright that he at once dropped the glass to the floor, spilling out the last of the wine. He dropped to the floor and at once started lapping up what he could, running his lips over the dusty floorboards of the Midwestern church, but the dry, desolate winds of late had sucked any moisture out of the air and caused the wine to evaporate almost as soon as it touched the ground. There would not be enough.

Zachariah’s pallor and sunken features took on a new horror as the cold calculations shocked him into a state of hyper awareness. It was finished. The reverend had no choice now but to endure what was to come. As the forces outside shook at the door, Reverend Zachariah calmly stepped down from his podium and lifted the lid to the casket.

“Blessed are the dead,” he said aloud, “for they shall be raised again.”

The aged reverend lifted himself into the casket just as the doors to the church gave way. Perhaps they will deal with me quickly, he thought to himself. Perhaps they will just leave me be.

The unholy shrieks of formless terrors enveloped the church and the casket in which Reverend Zachariah took refuge. He had heard from the earliest witnesses that these monstrosities defied biology and geometry as mankind understood the sciences, yet few who saw them retained reason or sense long enough to form a concept of these impossible nightmares. Wicked howls and a slapping like bat wings upon the wood of the casket signaled to Zachariah that the great horrors had arrived.

A man of faith such as himself tried to blink away the nightmarish beings that he imagined, but it was no use. What was worse was the ever-deepening need to see them with his own eyes. An obsessive urge pushed Zachariah’s hand up to the lid of the coffin, though he paused just before opening it. Gusts like hurricane winds were deafening. Curses and wails resounded throughout the countryside as ancient evils took over, still pouring from whatever abyss they had crawled from.

Though Zachariah did not see the most unnatural of the horrors when he lifted the lid just enough to see through, what he saw by the burning fires of the world outside was still to his great terror. The last image Zachariah saw while alive was the bodies of his church rising, following the horror out into the conflagrated world that was black as night with a wind of ash and soot.